During a crackdown on protests on 20 July 2024, Hossain, 24, and Bhuiyan, 19, took shelter at a Dhaka tea stall but police dragged them out, beat them and ordered them to run.

Bhuiyan was shot. Seeing him sprawled on the ground, Hossain began dragging him away, but police kept shooting. Hossain felt a bullet strike his own leg.

“I had to leave him behind,” Hossain says. Bhuiyan was later declared dead in hospital. Continue reading

Violence like this became the catalyst that turned student-led demonstrations into a mass protest nationwide. with its epicentre in the capital, Dhaka. Within a fortnight, the government had been swept from power, with Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina fleeing the country.

Up to 1,400 people died during the protests, the vast majority killed in the security crackdown ordered by Hasina, according to the United Nations.

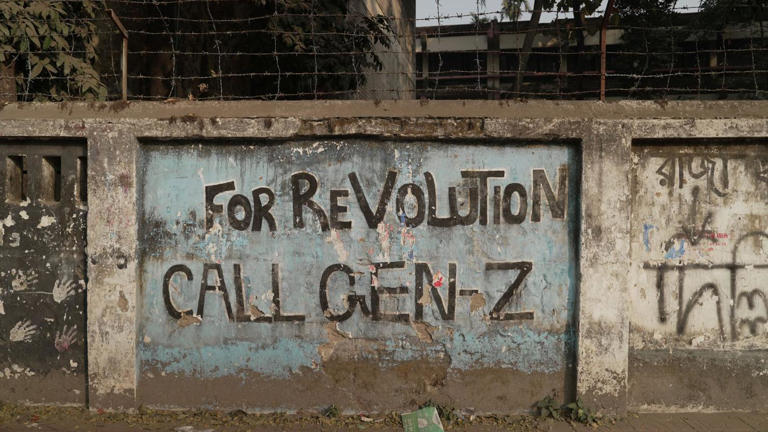

Hasina’s downfall seemed to promise a new age. The uprising was considered the first and most successful of a series of Gen Z protests around the world.

Some student leaders in Bangladesh went on to hold key posts in an interim government, trying to shape the kind of country they had taken to the streets to fight for. They were expected to play a role in the country’s future administration, after decades of rule by Hasina’s Awami League and the rival Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP).

But as general elections loom next week, the students’ newly formed political party is badly fractured and women in the movement largely sidelined. With the Awami League banned, other long-established parties are filling the vacuum.

Hossain joined the 2024 student-led demonstrations – which brought together young men and women, secular and religious – initially to protest against new quotas in civil service jobs, but kept going as they morphed into “a single shared objective” to end “autocratic rule”.

He isn’t alone in feeling the student-led National Citizen Party (NCP) is too inexperienced. Instead, he’s impressed by another, much older party: Jamaat-e-Islami.

It’s an Islamist party which has served as a minor coalition partner, but gained momentum of its own in the run-up to the 12 February election, from which the Awami League is banned.

Established in 1941, Jamaat has always been dogged by its stance during Bangladesh’s 1971 war of independence from Pakistan. Hundreds of thousands of people were killed, and more than 10 million fled their homes. Some of Jamaat’s politicians were accused of collaborating with then East Pakistan.

But that history does not seem to bother Hossain, who believes Jamaat has modernised.

“Jamaat supported the comrades of the July uprising and the students in various ways,” he explains.

Jamaat’s leader Shafiqur Rahman told the BBC the party is pledging to end corruption and restore the judiciary’s independence – claims that will be hard to deliver in a country with historically high levels of corruption, but which have resonated with many.

Professor Tawfique Haque of North South University in Dhaka says most younger voters, born long after 1971, can separate Jamaat from its history and don’t see it as a red line.

“It’s a generational issue,” he says, arguing they don’t want to be “bogged down with this debate”.

Instead, younger voters have seen the party as a fellow victim of Hasina’s rule, according to Haque, banned from politics and many of its politicians in jail.

Hossain is not the only one turning to Jamaat: candidates backed by the party’s student wing won a landslide during student elections at Bangladesh’s top universities last September, in a vote seen as a bellwether of the national mood.

Notably, it was the first time since independence that an Islamist party had won control of the student union at Bangladesh’s prestigious Dhaka University.

It was also the first major sign of trouble for the student leaders, in a country where about four in 10 voters are under 37.